For many people, the decision to move up to an SLR camera is the point where they start to take their photography a little bit more seriously. Certainly, many point and shoot cameras are capable of taking excellent shots, but for the best results, an SLR is usually the way to go.

For many people, the decision to move up to an SLR camera is the point where they start to take their photography a little bit more seriously. Certainly, many point and shoot cameras are capable of taking excellent shots, but for the best results, an SLR is usually the way to go.

In this article I will be providing an overview of the things you should know before committing to purchasing an SLR camera. I will take you through some of the jargon you are likely to encounter as well as the advantages (and disadvantages) of one of these cameras.

I will be focusing the article from the perspective of an upgrade from a standard point and shoot digital camera to a digital SLR camera. I am aware that there are other formats and camera systems out there, but so as to avoid confusing the issue, I will not be considering them.

First of all then, what exactly is an SLR, and what is the difference between it and a standard point and shoot?

What is an SLR?

SLR stands for SIngle Lens Reflex. All this means is that the camera uses a mirror and prism system to allow the user to see an image through the viewfinder which is the same as that which is captured onto the camera’s sensor when the shutter is depressed. This differs from other camera designs, where either a separate lens is used for the viewfinder, or the image is processed before being output.

The advantage of this “live” viewfinder is that there is no difference between the image you are looking at, and the image which you capture, and there is no time delay, unlike in a camera using an LCD as the viewfinder, where the image first has to be processed via the sensor and then outputted to the screen.

This mirror and prism system is the key design feature which separates an SLR from other types of camera system. From a practical point of view however, there are a number of other features that you will find on an SLR and not on a point and shoot.

Key difference 1: Sensor Size

One of the reasons people want to upgrade from a point and shoot digital camera to a digital SLR is the improved image quality. A key factor in this improved image quality is the increased size of the sensor that an SLR has compared to a digital camera.

The sensor, for those not in the know, is the thing inside a digital camera that records the light information. Once upon a time, the light information was captured by film, of the 35mm variety. These days, digital is the way forward, and the camera contains a digital sensor for this purpose.

Sunset over Mount Ruapehu, Tongariro National Park. The larger sensor sizes in an SLR camera are more flexible in limited light scenarios.

The size of the sensor is directly related to the quality of the image, influencing factors including how noisy the image is and how well the camera performs in limited light scenarios.

When I talk about the size of the sensor, I am referring to the physical size of the sensor itself, not how many pixels the sensor is capable of recording. Beyond a certain number, the number of pixels becomes largely a handy bit of marketing rather than anything meaningful to image quality. Sensor size is far more important than megapixel count.

Sensor size is, to confuse matters, not set to one size for point and shoot cameras and one size for SLR’s, but as a rule of thumb, cameras fall into one of three categories:

- “Full frame” (or APS-H) sensors are found on the most expensive digital SLR cameras. These sensors are physically around 35mm wide – the same size in fact as 35mm film. Hence the term, full frame.

- APS-C size sensors are found on the majority of consumer oriented digital SLR cameras. These feature a sensor which is 22mm wide, resulting in a total sensor area which is about 40% that of the full frame sensor.

- 1/2.5” sensors are found on most point and shoot cameras. These sensors really are tiny – only around 3% of the full frame sensor area. Hence the difference in image quality.

Key difference 2: Interchangeable lenses

Having boggled you with talk of sensors, I will now move on to lenses. Interchangeable lenses are an excellent reason to get an SLR. Depending on the type of photography you want do do, you can switch lenses from something that lets you take in really large panoramics (a wide angle lens) to something that lets you get up close and personal (a telephoto lens).

As with sensors, there is a world of jargon that you need to know about, particularly when coming from the point and shoot world.

Your point and shoot camera will have one lens option, which will usually be capable of optically zooming. It will have an optical zoom rating, normally provided, nice and simply, as a multiple. So if you have a camera with a 3x zoom lens, you know that you can point at a subject and make them appear three times larger. Easy.

SLRs do not adhere to this handy standard. Instead lenses are categorised according to two parameters: aperture and focal length.

Focal length

Focal length, which is measured in millimetres, will usually be the first thing that is considered when choosing a lens, as it is this that dictates the magnification of the subject you are photographing. This is rather similar to a point and shoot optical zoom rating.

Unfortunately, focal length does not easily convert to magnification factor, for a number of reasons, the main one being that different cameras have different sensor sizes. A 50mm lens on a full frame sensor camera would result in a different image if it were put on an APS-C sensor camera, for example.

On the whole however, and without getting too technical, the smaller the number in mm, the wider the resulting image will be, and the bigger the number in mm, the more magnification. To be considered wide angle a lens would usually have a focal length of around 28mm and down, whilst a telephoto lens would be 100mm and up.

The above two shots demonstrate the different focal lengths available on my 17-85mm lens. The first is a wide angle shot taken at the lenses maximum wide-angle setting of 17mm (35mm equivalent 28mm), whilst the second is taken with the lens fully extended to its maximum focal length of 85mm (35mm equivalent 138mm). This variety of magnification factors is a real benefit of a “zoom” lens.

As a note of reference, when comparing lenses and images, it is not unusual to refer to the “35mm equivalent focal length” of an image. This allows for a standard to be used for focal lengths across cameras with different size sensors. In the shots above for example, I am using an APS-C sensor – to achieve the same magnification on a full frame body, I would need to have a lens with a focal length as indicated in the brackets.

For those of you interested in these things, the mm value refers to the length the lens would have to be, in millimetres, if it was composed of only one piece of lens material. These days lenses are made up of multiple elements, thus reducing the physical size.

When it comes to focal length, lenses fall into one of two categories. A prime lens is one with a fixed focal length, say 50mm, whereas a zoom lens can vary its focal length.

A prime lens will usually have greater image quality with the trade off that you need to carry more lenses to cover your required focal lengths, whilst a zoom lens can result in image flaws at the benefit of being better as an all purpose lens for multiple tasks.

Aperture

The other factor to consider when purchasing a lens is the aperture. The aperture is the hole inside the lens that opens up to let light in – to use a well worn metaphor, it is much like the iris of an eye. The bigger the hole, the more light that goes in, the smaller the hole, the less light that will go in.

Outback sunset, Australia. This was taken at the maximum zoom of my camera with the aperture as wide open as it would go for that zoom length, which is a not very wide f5.6. A telephoto lens will usually have different maximum aperture ratings for different focal lengths.

I have a far more detailed post on how aperture and shutter speed work together when shooting. In brief, however, usually the bigger the aperture, the better and more expensive the lens. A bigger aperture means more light can get in, which means you can work at higher shutter speeds and in lower light conditions. You may seem people referring to a lens as being “fast”; what this means is that it has a nice big aperture. Conversely a “slow” lens will have a relatively large minimum aperture.

Aperture is measured by “f” stop, with numbers ranging from around 1.x up to around 32. The smaller the number, the bigger the hole. The majority of lenses have a variable aperture, and it is the smaller number, or f-stop, that you need to consider when purchasing a lens.

Key difference 3: Camera size

That was focal lengths and apertures. You can pretty much breathe easily now, because we are over the hard parts!

A clear difference between a point and shoot and an SLR is size. All that lens, mirror, prism and enlarged sensor have to go somewhere, with the end result that the bit of camera you are lugging around is no longer going to slip handily into your pocket. This may seem pretty obvious, but is worth bearing in mind.

Key difference 4: Speed

Speed is another serious advantage that a digital SLR has over the majority of point and shoot cameras. Because the camera is not caught up with trying to populate the LCD screen on the back of your point and shoot with everything that is going on around you, the time from pressing the button to recording the picture is not plagued by what point and shoot owners would refer to as “shutter lag”. Instead, when you press the button, you pretty much get the picture taken at that moment in time. So you are less likely to miss a key moment. Great news, particularly for sports or action photography enthusiasts.

Kite surfer off the Western Australian coastline. The fast reaction time of an SLR means photos like this can be captured as they happen.

Key difference 5: Setting control

Whilst some point and shoot cameras do give you more options in terms of controlling various settings of the camera’s features, they usually don’t come close to what you can do with an SLR. Pretty much everything can be adjusted, from aperture, to shutter speed to focal point, giving you seriously fine grained control over your images.

When an SLR isn’t better

Having now waxed on about the wonders of the SLR in terms of image quality and lens flexibility, I will now go through a number of reasons why an SLR may not be right for you in certain circumstances:

If you’re travelling light or you might lose it

If you are planning on travelling light, then an SLR could be an issue. Even if you only have the one lens, an SLR is always going to be a more significant burden compared to a point and shoot digital camera that you can slip into your pocket.

As well as this, an SLR is not the best for many situations where we want to document our fun times in an easy and portable manner, for example, on a night out. Rocking out in a nightclub or at a beach party with an SLR slung around your neck is hardly a practical option compared to the pocketable point and shoot option, and the risk that you put it down somewhere and it vanishes of it’s own accord is not one you are likely going to want to take.

If you need to be inconspicuous

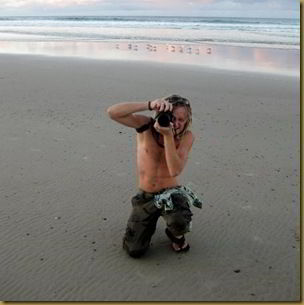

Let’s face it, there is no way you can be subtle with an SLR. Even if you decide to shoot “from the hip”, the noise a digital SLR makes, what with the mirror flipping up and the shutter opening and closing, is incredibly distinctive. So if you need to take photos without being obvious about it, an SLR is not likely to be the best option.

A self portrait in a series of mirrors in a bar in Cologne. Usually, an SLR isn’t the best choice for a night out!

If you need to do more than take pictures

Nearly every point and shoot digital camera these days can record film, and the majority of those even record film in high definition. The very latest models of digital SLR have started to feature HD film recording, but there is certainly a price premium attached to these models, even in the “consumer” ranges.

If you need something rugged

Most electronic devices are susceptible to the rough and tumble of everyday life, but cameras, featuring delicate bits of glass on top of the electrical wizardry, are particularly prone to damage. SLR’s, with their protruding lenses, do not take to being dropped very well, nor are they great at handling the elements, unless you go for the seriously expensive weather sealed professional level cameras.

On the other hand, you can pick up waterproof and shock proof “ruggedised” point and shoot cameras for little more than their standard variants. So if you want to be able to shoot underwater or you regularly bounce your camera off concrete, you may want to consider one of these instead.

Water exploding on the Western Australian coastline. Keeping my SLR dry in these sorts of conditions can be a bit of a challenge.

An easy solution to the above:

Personally, I get around the above issues by having both a point and shoot digital camera for the times when the SLR isn’t going to be appropriate, or when I want to film something, and take the SLR everywhere else.

Brands

There are a number of digital SLR manufacturers, but most people will find themselves choosing between the two major players in the space – Canon and Nikon, who between them account for over 80% of worldwide digital SLR sales.

The choice between the two manufacturers largely comes down to personal preference and what feels better in your hand. Both companies manufacture excellent products, and both have a wide range of lenses to suit your needs. A couple of notes on their ranges:

Canon

Canon’s digital SLR range is ordered by number, ranging from the 1000D through to the 1D. The D stands for digital. The less digits there are in the model number, the higher up in the range they are, with new models in each bracket receiving a higher model number. So for example, the 50D is a model range above the 500D, and the 550D is the successor to the 500D. Generally speaking, the three and four digit models are aimed at consumers and hobbyists, with the more expensive one and two digit models aimed at professionals. With the exception of the 7D, all of the single digit models are full frame.

Nikon

Much like Canon, Nikon’s range is denoted by number, although the numbering system is slightly less simple to decipher. There are basically four numbering ranges, from the single digit professional level cameras like the D3, to the four digit entry level cameras, like the D3000. After that it starts to get a bit complicated, with the D700 for example being a professional grade full frame sensor option, and the D70 – D90 models being the equivalent to Canon’s 400D – 550D range.

I have no idea why model numbers in the technology world are quite so confusing (Intel’s processor range is my favourite example of this), but luckily there are oodles of photography sites out there who can explain these things to you in more detail.

Choosing a lens

The camera body is clearly an important consideration, but of far more importance when purchasing your SLR is the lens. It is not uncommon, in fact, to spend more on the lens than the camera body.

When you are starting out, you may find that you will have the option to purchase what is known as a “kit” lens with your camera. This is usually a relatively cheap lens that will get the job done, and let you get to grips with your camera, but you will ultimately end up replacing it once you start getting more serious. You can save yourself a bit of money in the long run by opting to buy a more suitable lens from the start.

As well as considerations like focal length and aperture, lenses come with what may seem to be a bewildering array of acronyms. Often these just refer to the focusing mechanism that the lens uses, or whether or not the lens features an Image Stabilisation technology to reduce camera shake.

Deciding on a lens is entirely a personal choice, and comes down to the sort of photography you are doing, as well, of course, as your budget. Take your time and do your research. If necessary, rent a number of lenses for a period of time and see what you think. This is a serious investment, and needs to be treated as such. You can read more about lenses, as well as other accessories, for SLR cameras in this article, plus you can get to grips with a number of other photograph related tips in the rest of this series.

Well, that’s about it for my take on what you need to know about when it comes to digital SLR cameras. Let me know if you have any thoughts on this article in the comments below!

No comments:

Post a Comment